Muscling Through

Why do we exercise? Some books have the answer.

Muscles are having a moment.

As an ever-growing body of research accrues to document the positive impact of regular exercise of all types on bodies of all ages, testimonials to the benefits of strength training for women — in particular “older” women — have flooded my mediascape.

Should one want to start lifting, there’s no shortage of motivational and educational content out there, and while I’m still working up to move from dumbells to barbells myself, I’m an avid reader of various fitness and anti-diet culture newsletters, like Anna Maltby’s How to Move, Mikala Jamison’s Body Type, and Casey Johnston’s She’s a Beast.

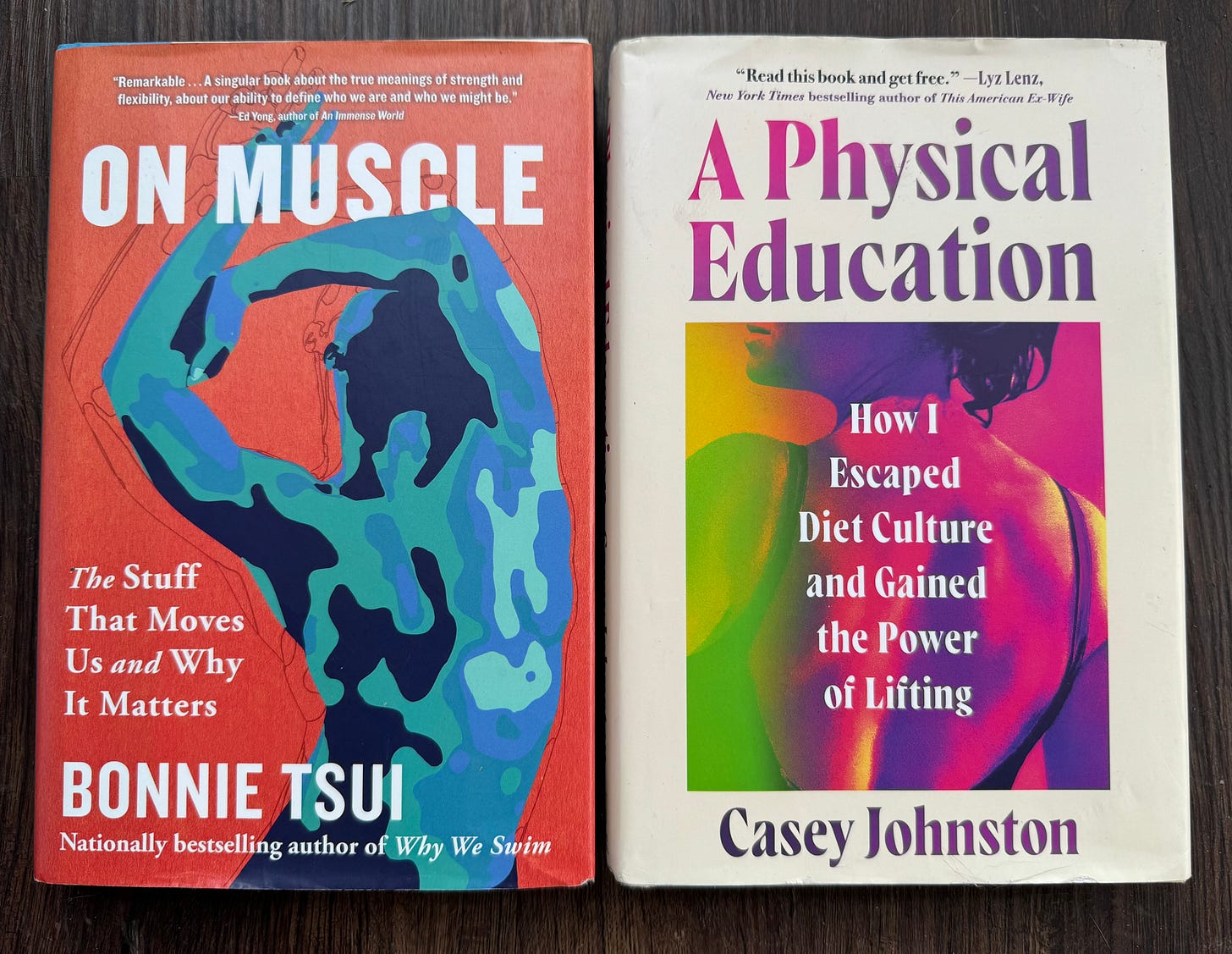

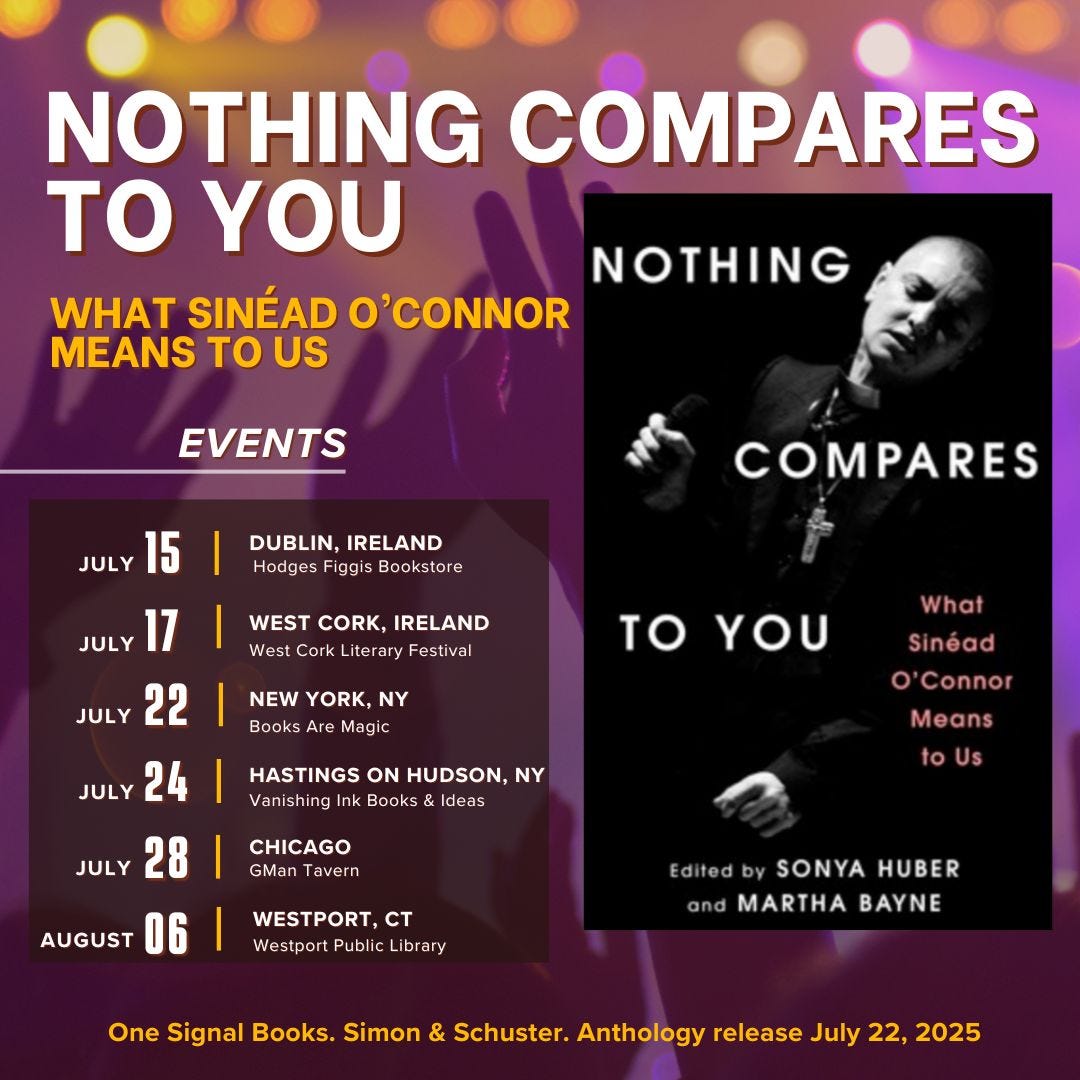

And it’s not just the newsletter economy that’s bulking up. Contra current publishing industry wisdom that nonfiction books aren’t selling and that bookstore events for said books are dead — a warning I hear from the publicist for the Sinéad book every time I try to schedule another release event — Johnston has seen standing-room-only crowds at events promoting her memoir A Physical Education: How I Escaped Diet Culture and Gained the Power of Lifting. I’ve been a fan of “She’s a Beast” for several years (and once sent her a sad little pitch to be the research assistant on the book). Here’s an excerpt, from the Cut. The kicker:

To be this big, to have and feel this much physical power, was a possibility I’d feared all my life. Except that where I’d always thought I’d see a monster, I saw a god, radiant like a big, beautiful horse. Doing everything I’d feared had allowed me to become exactly what I’d dreamed.

Johnston’s book, which I read earlier this month, is a wry, moving account of her journey into heavy lifting, a pitch-perfect example of one of my favorite genres: “follow along as I learn something new.” And as Johnston sorts out just how to do a proper squat and struggles to master the bench press, she also, of course, learns new things about herself: How to shed a lifetime’s load of shame and embarrassment. How to embrace failure. How to eat, for god’s sake. And, most interesting to me, how to heal the wounds inflicted by men, both in general and in the form of a real asshole of a boyfriend and her late, alcoholic, erratic father.

It’s a thread Johnston’s book shares with Bonnie Tsui’s new On Muscle: The Stuff that Moves Us and Why It Matters, an A+ representation of another of my favorite nonfiction gimmicks: take a noun (“Salt,” “Heat,” “Stiff”) and use it as the framework for understanding the world. Here Tsui, who took a similar approach in her previous book, Why We Swim, digs into the science and culture of muscle, and into its literal and figurative meanings. She writes:

Muscle means so much more than the physical thing itself. … We flex our muscles to give a show of power and influence. We have muscle memory; it’s a nod to the knowledge we hold in our bodies, of all things sensory, physical, and spatial. We lift ourselves up and jump for joy. We muscle through hard things; that shows grit. Even when it’s a stretch, we still try. And when we finally relax, it’s settling in, acceptance, letting go.

Tsui was indoctrinated into a physical life at a very young age by her father, a martial arts practitioner and fitness enthusiast who encouraged her to exercise and play sports throughout childhood and then, when she was in high school, moved back to Hong Kong and all but disappeared. Tsui’s longing for her father’s presence snakes through the book, a winding muscle of its own, flexing and relaxing. “The love of movement I have is really about my love for him,” she writes. “It’s the language he taught me. We keep practicing on our own until we can speak it to each other again”

Both Johnston and Tsui locate their physical practice in this quest for love — self-love, romantic love, father love. The development of muscle is a plain manifestation of the desire to be seen for who they truly are: to be the big, beautiful horse, to take up space, and to step into the life-altering potential of their own strength.

Or as Tsui writes, “Lately, I’ve come to understand that what I learned from my father was not just to lift heavy things, but to lift myself.”

Reading Tsui and Johnston, I was also reminded of a recent Chicago Reader essay by writer and powerlifter Micco Caporale, in which they frame lifting as a tool to heal from gender dysphoria and abuse. “Growing up,” they write, “my body was the subject of physical and sexual violence, so I’ve mastered the art of dissociation. It wasn’t until I began powerlifting that I learned how to tether my mind to my skin. Now, every time I pick up a barbell, I experience my body as a temple.”

I may be intimidated by the lifting corner of my gym, but I have become more and more lifting-curious thanks to testimonials like these, and I try to hit the gym at least twice a week. But it’s the psychological and, yes, spiritual gains that interest me as much as or more than the prospect of ripped delts (though those would be nice too). I came back to athleticism in my 40s in what I now understand as a key step toward tethering my own mind to my skin in the aftermath of sexual violence and, more generally, twenty-odd years of dissociating from my body in the hope that by ignoring it, or numbing it out, I’d magically not have to make peace with it. I started running, and then got into triathlons for a time (so expensive …), before wandering into a circus gym and finding something I recognized as akin to the dance studios of a former life. And then I went there as well.

I didn’t do it to lose weight or get snatched, but I’m sure that more useful health benefits have accrued. It obviously didn’t stop me from getting cancer but I’m told having a baseline level of relative physical fitness helped me tolerate treatment as well as I did. And, so far I haven’t had a recurrence — something about which there is plenty of ongoing research, witness the recent study of the effects of regular exercise on colon cancer patients, hailed with sweeping headlines claiming “Exercise Extends Life for People With Cancer.”

In a recent essay on her newsletter Residiuum, Kaya Oakes — whose writing on both cancer and religion I have come to consider a must-read — took aim at that study, noting, with characteristic pith that “now we have to live with the knowledge that if the cancer comes back, many people will sigh and say, ‘well, you know, she never ran a marathon.’ The day when I didn’t work out might be the day a cancer cell woke up somewhere in my body, and once again, the failure to survive will be the fault of a body that just couldn’t conquer itself.”

But I would gently counter that when I exercise I am not trying to conquer my body, I am trying to become one with it.

Having spent eighteen months debilitated by chemo and radiation and multiple broken bones, the chance of finding pleasure in the strength of my body — whether through lifting or swimming or dancing or flying through the air on a trapeze — is a source of joy (endorphins are real) but also a space of transcendence. To quote Capporale again:

I wasn’t a spiritual person when I started powerlifting, but I’ve become one in recent years. It’s hard for me to see these things as unrelated. Western thought treats the mind and body as separate, but many Eastern traditions do the opposite. The Enlightenment era advanced this idea through Cartesian dualism (“I think, therefore I am”), but it was already present in Christianity via the duality of God and humanity or heaven and earth. In a nondualist perspective—which is at the heart of Zen and many other Eastern spiritualities—the body and spirit are one and the same. Enlightenment is a spiritual awareness of the nature of reality (that everything is one) and can be part of the path to God-realization.

Like Capporale, and Johnston and Tsui, exercise has been my key to all sorts of healing of body, mind, and spirit. While I know I will not outrun death, I exercise because in the full awareness of that inevitability it makes me feel the most alive.

I’ve spent so long trying to pull this piece together that I wound up cutting almost all the the stuff about cancer, like my trip to the American Society of Clinical Oncology conference last month! I went to ASCO on a guest pass with Anna Wassman-Cox, the founder of the OncoBallet program I will hopefully be teaching in this fall. In addition to being very overwhelmed for the better (30,000+ people working on curing cancer) and the worse (I don’t even want to know the price tag on the show floor pharma booths, with their latte stations and free soft serve cones), I sat in on a session on how to integrate exercise into oncology treatment, featuring the popular factoid that less than 30% of the general population exercises on a regular basis, whether they have cancer or not.

Like basically every clinician I’ve encountered in my own treatment, the panelists operated from the assumption that their patients were among the other 70%, and that both they and their unenlightened oncologists needed to be brought up to speed on the bare minimum benefits of 30 minutes of movement a day. “I know of no other supportive activity that has the same mortality benefit [ed: ugh] as an exercise program,” one of the panelists said, according to the note in my phone. But as I sat there in the room listening to them champion the need for a paradigm shift, I couldn’t help feel their solutions, like offering cancer patients a “workout kit” that included a resistance band and some sliders, were all so … un-fun. Exercise is medicine, sure, but does the prescription have to taste so bad? “In a few years,” I whispered to Anna, “they’re going to be talking about dance like this, and it’ll be so much better.”

Thanks for reading! So much going on right now including, this morning, a nice early review of NOTHING COMPARES TO YOU in the Chicago Reader. The book is out July 22. It would mean the world if you were able to come out to one of our events. Updated schedule below!

I'm woefully out of the habit of regularly exercising. I know I need to get back in the groove. Thanks for this post. <3

Thanks so much for the shout out. I was lifting my puny three pound weights today (thanks, high risk of lymphedema) and realizing hey, this is a lot easier than it was a few months ago. Which means I am actually building muscle. If PT ever clears me to lift anything heavier, I'd be curious to find out what that feels like. This was good inspiration.