Goodnight, cool

Does the "cancer memoir" need to be disrupted?

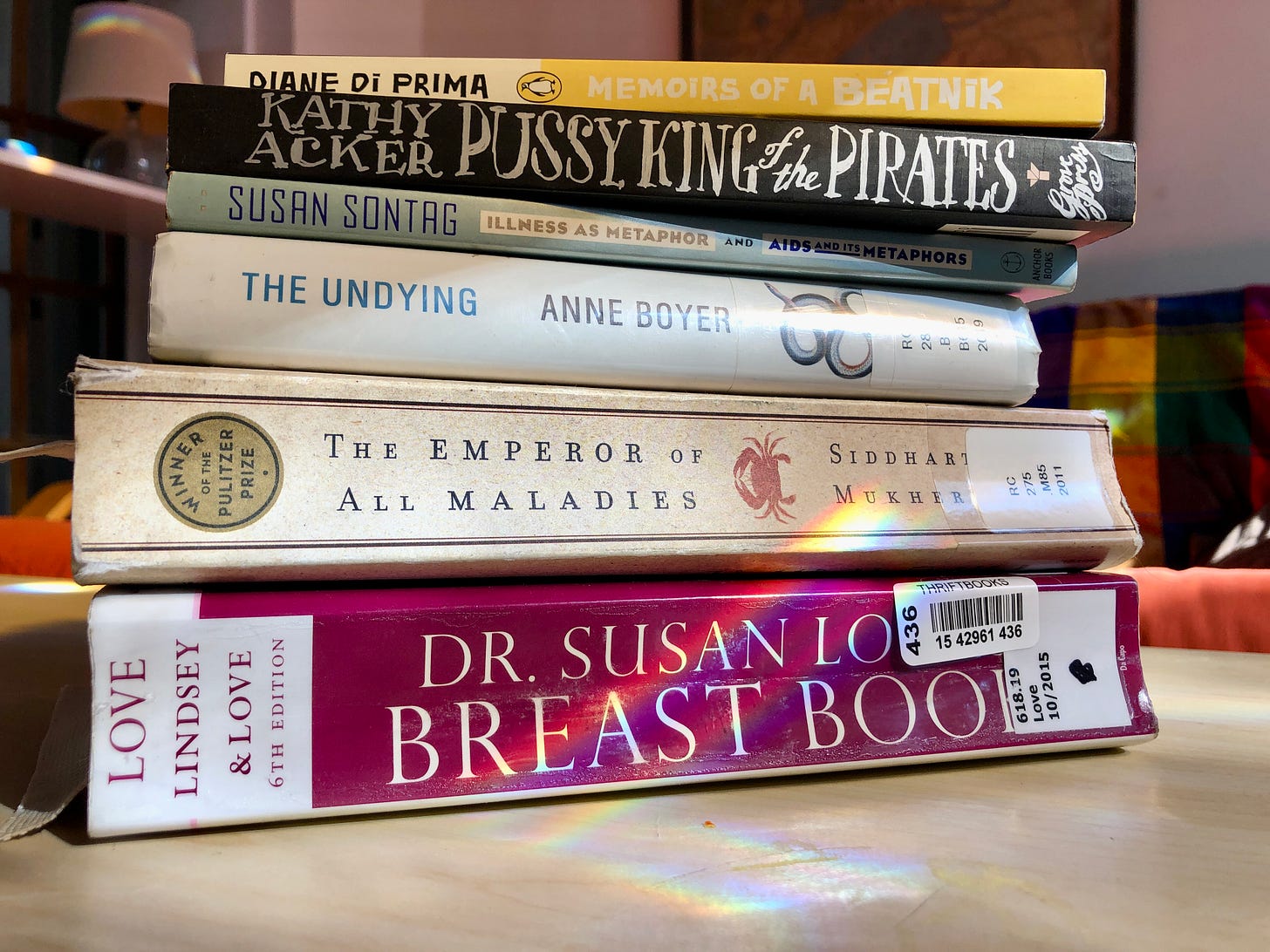

It won’t surprise anyone who knows me to learn that my m.o. when confronted with a new problem or project is to go out and acquire a whole bunch of books. Thus far, the breast cancer project/problem has led me to not just the very useful Dr. Susan Love’s Breast Book and Siddhartha Mukherjee’s epic “biography of cancer” The Emperor of All Maladies but – in a perhaps less practical vein – Paul Kalanithi’s When Breath Becomes Air and Anne Boyer’s The Undying.

The former has been on my reading list for years. Kalanithi’s memoir of his diagnosis with stage IV metastatic lung cancer, on the cusp of completing his medical residency, was roundly acclaimed when it came out in 2016, after being completed by his wife Lucy after his death. It is frank, wry, philosophical, moving, and laced with just a touch of stereotypical neurosurgeon’s arrogance. Am I speaking ill of the dead? I don’t think he’d mind; he cops to his arrogance himself in the book and, as I’m not a neurosurgeon, you should probably take my judgment with a grain of salt. Besides, the core of the book is Kalanithi’s unqualified endorsement of the importance of finding, nurturing, and celebrating joy in the middle of the darkness. A subject I hold close, and one that so far I’ve been a little embarrassed to fully explore here (more on this later).

When I mentioned the book to one of my chemo nurses she joked, “Ah, going for the fun ones!” If I was really interested in depressing cancer memoirs, she added, maybe I should look at The Undying. She herself, she confessed, hadn’t been able to finish it; she was put off by (her words) Boyer’s anger. But, she said, I might find it interesting.

Challenge accepted. I’ve now read The Undying twice and have been trying to write about it for a month. Interesting it is, for sure – and not in some passive-aggressive Midwestern definition of the term. Boyer, a Kansas City poet and essayist, plays with form and language with voluptuous ferocity. Narrating her journey, at age 41, through diagnosis and treatment of aggressive triple-negative breast cancer, she resists pat moralizing and pushes back, furiously at times, against received wisdom.

In part the book is a brutal catalog of the agonies of treatment: the baldness and the vomit. The alien bulb that juts from the sternum, the steroids that swell the face, the acne that (thank god) hasn’t happened to me yet. The rashes, the sunburns, the crushing, mind-numbing fatigue. The diarrhea. (Does she mention the diarrhea?) It’s such an assault on vanity, an assault on the self that at times I wonder why I don’t, like Boyer, wear blonde wigs and bright blue tights to treatment, to loudly remind myself, and anyone looking, that I don’t just exist, I am special and I am beautiful.

But it’s also a full-throttle literary experiment in remapping her, and our, understanding of this ordeal. She stabs her prose with references to John Donne and the Greek orator Aelius Aristedes and a YouTube vlogger named Coopdizzle and the Tibetan Book of the Dead. She references Sontag, of course, and lauds Kathy Acker’s cool lack of sentimentality about the cancer that killed her. In a moment I loved, she quotes Diane di Prima, writing, “Immobilized in bed I decide to devote my life to making the socially acceptable response to news of a diagnosis of breast cancer not the corrective ‘stay positive,’ but these lines from [di Prima’s] “Revolutionary Letter #9”: “1. kill head of Dow Chemical/ 2. destroy plant/ 3. MAKE IT UNPROFITABLE FOR THEM to build again.” At times I can feel the effort pulsing off the page, a living thing, and it’s all I can to do to ride along with the loping cadence of her words.

For weeks I could not figure out why I did not adore this book.

But I think I have an answer, finally. In The Undying, Boyer is challenging not just the medical-industrial complex, but the cancer memoir complex as well, an endeavor in which she, too, is engaged even as she rages against it. In the first few pages she takes aim at the genre’s engine of testimonials and personal histories, which center the “I” in the endlessly iterated sentence, “I was diagnosed with [KIND OF CANCER] in [YEAR], at the age of [AGE].”

“Breast cancer’s formal problem,” she writes, “is also political. An ideological story is always a story that I don’t know why I would tell but I do. That sentence with it’s “I” and its “breast cancer” enters into an “awareness” that becomes a dangerous ubiquity. As [S. Lochlann Jain, author of a book called Malignant] describes it, silence is no longer the greatest obstacle to finding a cure for breast cancer: ‘cancer’s everywhereness drops into a sludge of nowhereness.’”

She’s trying to disrupt the cancer memoir, even as she crafts one out of her own clay, and that tension – that self-aware, high-wire hypocrisy – crackles through the book, putting an electric fence around any emotional core. Any, god forbid, sentiment or extension of the self toward the collective experience.

Because if the testimonial is the engine that drives the cancer memoir, identification, or its absence, provides the catalytic spark. A cancer patient (me) reads another’s story and classifies: are they like me, or not like me?

I do this. I did it with Paul Kalanithi, decidedly “not like me” (male, brown, neurosurgeon, dead). And I do it with Boyer, but am confounded to find that, while in so many ways she should be “like me,” I am for some reason rejecting our commonalities of femininity, of whiteness, of writerliness, of living, at some degree of opposition to the mainstream.

In part, I realize, I don’t fully trust her? Boyer positions herself as a truth teller, but her truths aren’t true to my experience. Her port hurts, she says; the doctors lie, and tell you it doesn’t hurt, but it does. But … my port doesn’t hurt. She mentions the effect of steroids on her face several times; it is clearly a point of injury. I look in the mirror and, yes, my face is kind of puffy. But it doesn’t really bother me. Am I beyond vanity? I don’t think so. Her cancer is scarier than mine, I think; her chemo must be of a function more intense. But, says the nurse, when I go back to unpack this with her, it’s not any worse than what you’re doing.

When I was learning to be a journalist, I was drilled with the idea that if you spell someone’s name wrong in a story, 99 people won’t notice, but the one who does won’t trust your authority on anything else. It’s a little like that but looser. While reading The Undying I keep casting around for common ground, but in her determination to carve out this new understanding, she undercuts it at every turn. My fruitless attempt at identification makes me feel uncomfortable and lame, like I want something cheaper, more mass market from this memoir project than she is interested in giving.

If I was cool, like Boyer, or Kathy Acker, I wouldn’t need sentiment or solidarity. But, you know what? I worked (briefly, glancingly) with Kathy Acker when she was very ill, and she was so sick and frail and weak, her famous bodybuilder physique wasted away, and as far as I could tell plainly refusing to talk about how dire her situation had become. Is that cool? I don’t even know anymore. What I do know is that I am grateful not just for the generosity of other writers, but for things like my rowing team, and not just the whole team but in particular the two other women on the team who have had my same diagnosis and treatment. There is safety, and power, in numbers, and if I’m thus living in “cancerland,” so be it.

I’m obviously projecting some here, but essayist/author Heather Havrilevsky wrote a trenchant thing this week about writer’s block, about shame, and about wanting to keep secrets and yet needing to tell the truth, that helped this all click into place. She was diagnosed with, and treated for, breast cancer in the last year or so (that boring ubiquity again) and is only now starting to talk publicly about it. She wonders aloud if she will ever write about her experience. Maybe, she writes, it’s a chapter in her story that doesn’t need to be told.

For much of my writing life I’ve loudly defended this idea that you are allowed to keep secrets. You don’t need to lay your trauma out on the table for public approval; that it can be damaging, in fact. It’s better to play it cool.

And it cuts both ways: for months before I got married I didn’t say anything about it in the public square. Plans were taking shape, dresses were being bought, and I was overflowing with feelings and thoughts about the whole situation – me, getting married, in a white lace dress, at 54 – but I couldn’t bring myself to write about it. I told myself I was keeping it private, and that is very true, but also, I felt shame. Who was I to be happy as the world burned?

This past year has been rough on both the country and on my inner circle, now in the full cataclysm of middle age. Friends have weathered life-threatening health crises, of their own and of their children or their parents, or both. Relationships have become tattered; marriages frayed. And that’s not even getting into the story of the babies born in a war zone. It’s been a lot, even if I’ve just been a supportive someone adjacent to various persons in crisis. It would only be polite, my inner monologue muttered, as winter ran into spring, not to impose my happiness on them. Wasn’t there something unseemly about finding joy in the middle of so much macro and micro collapse? Better to keep quiet; not pull focus.

I almost even backed out of the pre-wedding weekend my friends planned for a late May weekend at a house in rural Michigan until, as more than one of them told me, “we need this as much as you do.” At that weekend, which was glorious, one friend was struggling with her own recent breast cancer diagnosis. Another was mourning the impact of her chronic illness on her creative life. And over the course of the weekend one friend’s father landed in the emergency room and another’s mother at what appeared at the time to be death’s door.

I wrote something in my journal that weekend about feeling paralyzed, ashamed to express joy but also afraid to share my own struggles. I was about to get married, something I’d never done before, never thought I’d do. I was a little scared! Also, I had a mammogram scheduled for the day we got back, to look at this mildly alarming lump in my breast, and even though of course there was no way I was going to have breast cancer too, I was a little spooked. But my friends needed this restorative time as much as I did, or more, so I wasn’t about to dump my bundle of anxieties all over them in the hot tub.

Well we know how that all worked out.

But the side effect of the diagnosis has been to flip the switch. Where I kept a zipped lip about the looming marriage, I can’t seem to stop talking about cancer. It’s fascinating, for one thing. And for another, it helps: it helps me, and I’ve been told it helps others as they too parse out what part of my story is like them, and which is not.

The Undying, I think, may speak more clearly to those on the outside – those who are past the embarrassing need to seek common ground to make sense of their own experience, or who never needed it in the first place.

“When it was happening, all I could write was abstract prose,” writes Havrilevsky at the end of her essay. “I had it relatively easy, but it was still hard. I haven’t been ready to tell anyone about my body, which is about the most private thing there is, at least for me. But I’ll probably write about it eventually, even though some part of me thinks that’s distasteful, and it would be cooler if I didn’t.”

She’s right, it probably would be. But I hope she does write about it. I don’t know Havrilevsky but I’ve been following her work since the days of Suck-dot-com, and I get the sense that she, like me, actually has little use for cool anymore. Better to be honest — as she too urges — and risk the shameful ubiquity of claiming the “I” in your story. It’s intoxicating, and when you can’t drink or smoke any more, it’s one of the few thrills we’ve got left.

—

Whew! That was a lot. I’m still working my way through Emperor of all Maladies, and I’ve got Harvey Pekar and Joyce Brabner’s book (Our Cancer Year) on hold at the library, but I’m taking recommendations for the reading list. Need not be cancer-related! I could use a little frivolity, frankly. Drop suggestions in the comments my friends, and thanks for reading.

Martha - surprised to find your substack here today. Subscribed! First, happy to read of your marriage: mazel tov. Saddened by news of your cancer. From your rowing crew, I'd guess you're already familiar with Sandi Wisenberg's 'Cancer Bitch.' Another Readerite suggestion, Matt Freedman's 'Relatively Indolent but Relentless.' A huge help to me in my cancers and transplant was Christian Wiman's 'My Bright Abyss,' both essay and book. ...Wishing you well.

Suggestion: 'The Two Kinds of Decay', Sarah Manguso.

Keep writing - and yes you will beat this.... C. Cook