Once a year at the beginning of October I go downstate to Springfield for work. The same conference happens every year, full of the same 100-odd people. The weather is always glorious, the leaves just starting to turn orange and gold against blue, blue skies. And the town is always ghostly quiet.

Springfield is the capitol of Illinois, but it’s no DC, or even Madison, Wisconsin. Few politicians actually live here. Even when the legislature is in session their presence is imperceptible. I assume they transit straight from plane, train, or automobile into chambers without touching grass — or in the case of Springfield, decrepit pavement. In the shadow of the domed capitol building, the town is held together by a handful of middling restaurants and sparsely populated bars, one cool coffee shop, a decent used bookstore, and a lot of vacant storefronts. And, of course, Lincoln.

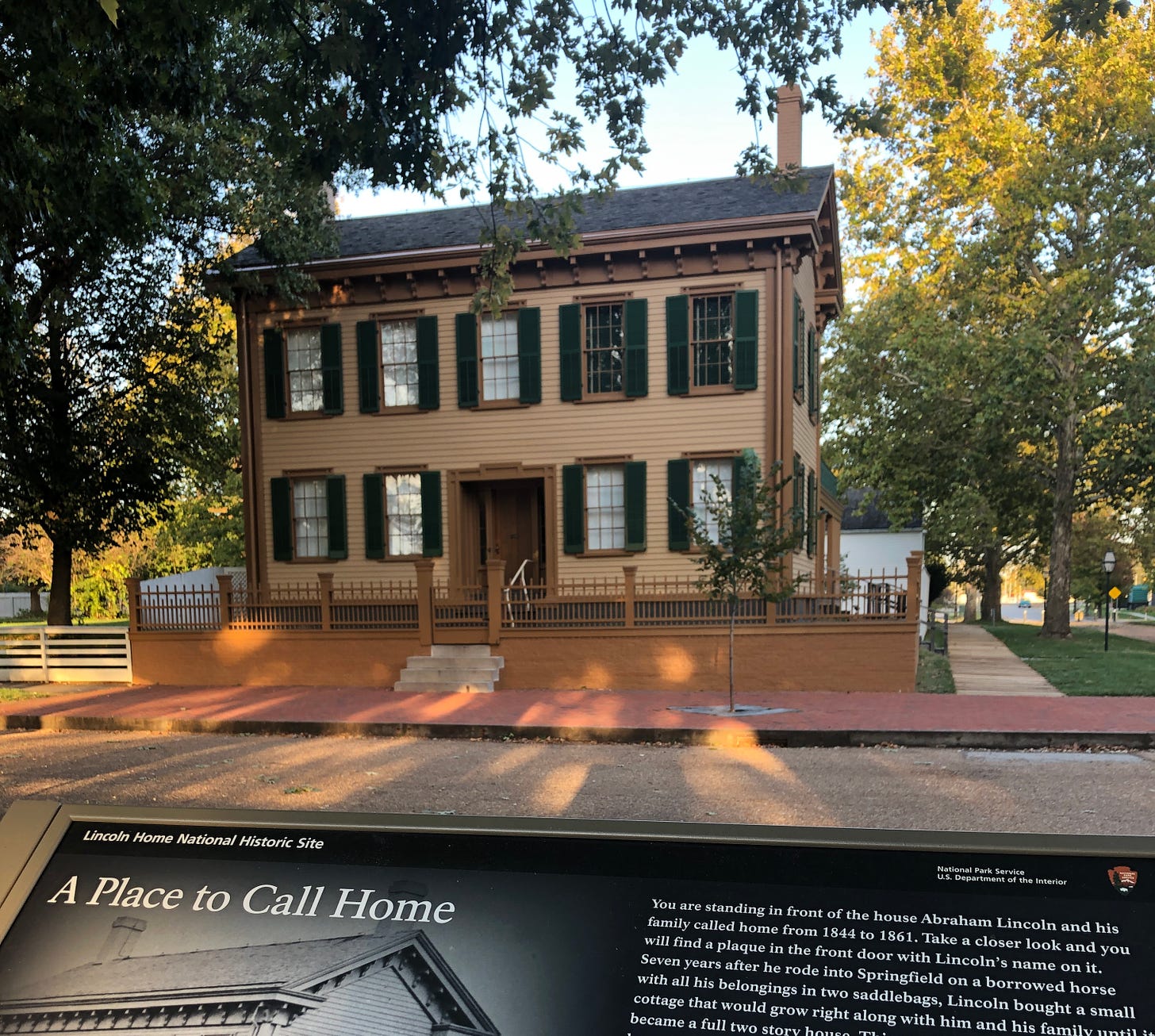

More than 150 years after his presidency and assassination, Abraham Lincoln is the town’s reason for being, its beating, bearded heart. The conference I attend is held at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, not to be confused with the Lincoln public library a few blocks away. The Lincoln Home National Historic Site takes up four and a half blocks on the edge of downtown, surrounding his former house on what is now the corner of 8th and Jackson. There is a modern visitors’ center, but the rest is just the old hood, restored and frozen in amber. The streets are closed to cars, the sidewalks are plank. Placards outside various Civil War-era residences discuss the place of the Lincolns in their neighborhood: who Mary Todd’s friends were, the surprising racial diversity of the block.

I’m always working during the day, so I’ve never taken the tour inside the house. But I like to wander up here in the evenings when the visitors center is closed and the schoolkids on field trips are gone. There is rarely anyone around save some vocal and aggressive squirrels. It’s so still at dusk, the silence punctuated by crickets, church bells, a train whistle. It feels both out of time and of all time, this memorial to the daily life of the nation’s most beloved leader, the Great Emancipator, Honest Abe himself.

Last week, two days after the vice presidential debate saw an oily opportunist lie repeatedly, without shame, to the nation, the site felt somber. Here in this quiet place, in a nowheresville town, surrounded by corn, the democratic ideas of Lincoln feel hopelessly antique, themselves as much a carefully preserved relic as the modest wood farmhouse the Lincolns called home. I’m no Lincoln scholar, but while I sat on my bench I was moved to look up Lincoln’s thoughts on democracy, from a moment when the nation was locked in terrible, intractable conflict, a moment that led to war. I found this, from 1858:

“As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy.”

The plainspoken clarity of these words echoes through Tim Walz’s yes-or-no question to his opponent last Tuesday: Did Donald Trump lose the 2020 election? The antihierarchical model he espouses finds uncanny anarchist mirrors in the mutual aid networks mobilizing to support North Carolinians devastated by Helene, just as they did for victims of Maria, and of Sandy, and of Katrina, and they surely will after Milton. And it rings through the words of Ta-Nehisi Coates last week on CBS Mornings, as he was aggressively (patronizingly, racistly) grilled on his support for Palestinian liberation in his new book, The Message. “I have a very very very moral compass about this — and again, perhaps it’s because of my ancestry,” he said, invoking Jim Crow. “Either apartheid is right or it’s wrong.”

Sitting there with the squirrels I wondered if it could all be that simple. I feel simple even sharing the thought, and not in a clean-lines and minimalist way. But it actually can be that simple: We should tell the truth, we should take care of one another, and we should defend the fundamental tenet of democracy, so clear in theory and so forever compromised in action, that all are created equal.

A few days after I came home from Springfield I went into the city for the opening day of the Chicago Sukkah Design Festival, in a beautiful plaza in the historically Jewish, and now majority Black west-side neighborhood of North Lawndale. Founded by a couple of social justice-minded architects, Sukkah Fest — now in its third year — invites local designers and artists to collaborate with neighborhood partners to built creative sukkahs, the traditional huts built to celebrate the Jewish holiday of Sukkot.

I was part of a design team for this year’s festival, but most of the creative work and physical construction was done by my friend Andrea Jablonski, a brilliant visual artist who is also part of the ongoing Soup & Thread project. Created in collaboration with folks from the nearby Douglass Park branch library and artist-educators from the School of the Art Institute outpost at Homan Square, our sukkah is titled “A Sharing Sukkah,” and features space for a seed library and a book exchange, as well as bulletin and chalk boards for sharing news and thoughts. When the festival is over at the end of the month it will be relocated and permanently installed in a garden next to the library.

I think it is gorgeous, and I’m honored to have been even a small part of creating this beautiful space for reflection and sharing. But at the same time I was sort of uneasy. I’m not Jewish; should I really be doing this? Is it unseemly in some way to host the opening celebration the day before October 7, a day of terror for Jews in Israel and a day that launched a year of terror for Palestinians in Gaza, and for those still held hostage there. The sukkah is a temporary hut representing the improvised dwellings of the Israelites on their flight from slavery in Egypt. It provides shelter from the elements and a space for being in community with family and friends. As I sat in ours on on Sunday, I marked the peace our shady structure provided, and what it must be like for those thousands now wandering Palestine with no shelter or respite in sight. What might it take for their homes to be as valued as the homes of Great Men?

I’m sick with a head and chest cold now, my own travels having taken an inevitable toll, and my thinking is thick and fuzzy. But on Sunday as a diverse crowd of Chicagoans wandered the plaza, exclaiming over the designs and sharing food from the jerk chicken truck, I felt at least locally the possibility of peace across borders.

At one point Afrofuturist dancer/author/filmmaker Y’tasha Womack led a multiracial and -generational group of dancers through a visioning process, asking us to articulate our dreams for the future and then represent them through movement. We stood in a circle, a bit sweaty from the warmup, and small group by small group we reached arms to the sky for peace, encircled each other for love, crossed arms to stop the violence, and stamped our feet for empowerment. The dancers’ smiles shone as bright as the sunny day. It was simple, and so very beautiful.

We’ll be hosting a Soup & Thread sewing bee on Monday, October 14, from 1-3 pm at the sukkah plaza at James Stone Freedom Square, 3615 W. Douglas Blvd. in Chicago, in conjunction with the weekly Sustenance for the Soul meal served there by Stone Temple Baptist Church.

so lovely to read this...